If the overarching weapon once used to control powerful kingdoms was now adorned as a garland of resilience, it would look like Sri Lanka. The colonial influence on Sri Lankan culture is a much-discussed yet less-researched topic worth visiting in an article.

From Tamraparni (Sanskrit) → Tambapanni (Pali/Sinhala) → Taprobane (Greek),

And then from Serendib (Persian) → Ceilão (Portuguese) → Zeylan (Dutch) → Ceylon (British),

The teardrop island evolved through multiple identities until it identified itself as Sri Lanka at the end of the colonial era.

Beyond the names, a striking testament to the identity arc is tea: The 1860s could have seen this island as the second-best producer of tea for the British, but the 2025 Guinness World Record recognises New Vithanakande Ceylon Black Tea as “The most expensive tea sold at a tea auction”.

Sri Lanka does not reject its past. Be it mythology (Ramayana) or reality, it has always risen from its ashes. One must unweave the history of Sri Lanka layer by layer to understand the depth of its modern colonial colours. Or simply walk its streets and live it.

Why Sri Lanka?

Colonisers may come, colonisers may go, but the land never loses its value. Then, now and even in the uncertain decades ahead, Sri Lanka will remain a sought-after nation for three reasons.

1. Strategic Location

For a long time, primarily due to its position in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka has served as a crucial maritime crossroads, connecting East Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Empires that sailed its waters established ports, naval stations, and fortified outposts along its coastlines.

Today, the Pearl of the Indian Ocean continues to command attention with bustling ports, trade hubs, and investment in logistics, shipping, refuelling, and energy infrastructure. The growing presence of Indian and Chinese enterprises in Sri Lanka is a testament to this.

2. Wealth of Natural Resources

For colonisers from snowy lands, Sri Lanka’s fertile soil and year-round tropical climate proved irresistible. Its plantations of tea, rubber, coconut, and cinnamon transformed the island into one of the British Empire’s most profitable anchors.

Centuries later, that same natural abundance endures — in mineral-rich highlands, gem-studded rivers, and coastal fisheries that sustain both local livelihoods and global trade. Today, the island’s winds and waves even promise a new kind of harvest: renewable energy.

3. Biodiversity

Can you imagine the folly of colonising a land so rich in biodiversity that a part of it reminded them of their homeland? Nuwara Eliya’s climate made the Britishers nostalgic enough to import plants and trees from their motherland, build cottages and gardens to mirror their faraway isle, and also name it “Little England”. That was not it.

Today, those same ecosystems stand at the heart of Sri Lanka’s renewed identity, protected in national parks, studied by conservationists, and reimagined through sustainable travel. Resilience is nature’s oldest instinct.

Ceylon as a Colony

The greed for natural wealth mixed with a superiority complex — be it with respect to civilisation, science, religion, race, language, or law — has always been the fuel that kept the fire of colonisation burning from every direction.

If we were to dig into Sri Lanka’s colonial history, we would have to trace every community that dominated and integrated with the then-existing society, beginning with whoever overpowered the Balangoda Man. There were multiple North- and South-Indian invasions, Aryan invasions, and eventually the popular European invasions as well. To unpack the current mosaic culture, let us look into just the European colonial influence on Sri Lankan culture.

The European Masters

What more could exhilarate European powers than a land of fragmented kingdoms, each ripe for manipulation and control? In fact, the ingredients of conquest were all in place with a ready-to-exploit local economy and a table wide enough for cultural and religious influence opportunities.

Valour was never the island’s weakness. More than military forces, the colonisers had to employ multiple coercive strategies to get their authoritative hands on Lanka’s natural treasures. Besides giving rise to people of mixed races like Toepas, Mestizos, and Burghers, who had to deal with complex identity issues, the colonial influence on Sri Lankan culture painted Lanka’s tangible and intangible heritage with the colonisers’ “superior” faith, cuisine, architecture, music, education, sports, law, language, and lifestyle.

Although the 443 years of colonial impact forced a colonial mentality on the islanders, they were inherently aware of their own culture’s weight. Post-independence, Sri Lankans chose to unlearn and relearn their languages and revive their culture through religious movements. Yet, some colonial colours just don’t wash off, do they?

Colonial Influence: Scars or Tattoos?

Superficially, a modern Sri Lankan native might seem to have an identity utterly unique to the island. But if a French woman were to visit a long-time Sri Lankan friend, she might casually be greeted with an air kiss and later offered “paan” — a word that traces its origin to the Portuguese “pão” or maybe the French “pain”, meaning bread.

Portuguese surnames, Dutch law, and British culture each have left their own indelible marks on Sri Lankans. But the beauty of the concept of culture itself lies in the changes it undergoes throughout various eras. So, now, it is all about flaunting it right.

The Art in Architecture

Ironically, what once symbolised subjugation now generates revenue for the nation via tourism. Art is art, and a land with a timeless heritage knows how to respect and preserve it without discrimination. As a result, today, pastel cafes are humming the oldies from the Gold FM inside the Dutch walls built for war.

From colonial railways turned lifelines of travel to plantation estates reborn as luxury retreats, there is a visible acceptance of the colonial influence on Sri Lankan culture, as the country continually redefines inheritance as innovation.

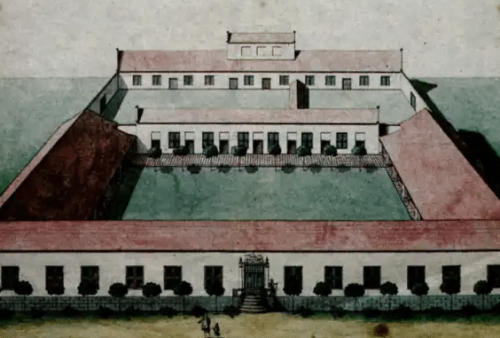

Galle Fort

Officially recognised by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Galle Fort is an ideal example of colonial architectural legacy, as its bastions have witnessed the iron hands of all three major colonisers. Originally built by the trade-minded Portuguese in the 16th century, the fort features sea-facing walls of coral stone, tunnels, underground storage, and, of course, bastions. Under the Dutch-Ceylon, the fort was refined with Dutch architectural style etched into every stone of the cobbled paths, ramparts, verandahs, and open courtyards. Those familiar with the British architectural style cannot help but notice the archways, collonaded verandahs, and high ceilings. Presently, its Black Fort is serving as the official residence for the Southern Province’s Senior DIG of Police.

The Dutch Hospital, Colombo

Opened in 1861, this hospital is now a shopping mall, walking into which you may gape at the high ceilings and massive teak beams while browsing for Batik wear. The spacious central courtyards and the long, open verandas effortlessly set the mood for the dining experience it now provides.

Retention and repurposing of most of these colonial buildings serve a more meaningful cause than merely romanticising European architecture. They provide an everyday reminder of a scary past that the nation has begun to embrace as its own. Take the love story behind the Mount Lavinia building — Lankans love sharing it.

The colonial structures that are in use, like the Tudor-style red-brick Post Office, Dutch canal system, Old Parliament Building, Cargills Building, Queen’s Cottage, and the Hill Club, integrate colonial charm through features like antique furnishings, stained-glass windows, wide guest doors, steep roofs, gables, verandahs and Doric orders. Meanwhile, the non-restored colonial ruins, such as Arippu Fort and Kotugodella Fort, narrate stories that any discerning traveller cannot help but pause for.

The Classic Weapons of Culture

The ornate colonial buildings that stand tall are mere husks compared to the imposed laws, education, and religion that once served as the veins of colonial rule. Imperceptibly, they continue to play a subdued version of their role in the modern Sri Lanka, like the reflex action of a tail severed from its reptile. The first-world countries (as per the West-established hierarchy), whose factories pollute the neo-colonies’ land and water, still profit from their natural wealth, except that the freedom from this modern colonisation is not a possibility.

Law

The major linguistic influencer, the Portuguese in Sri Lanka, took a ruthless path to till the soil for colonisation — reshaping Ceylon’s social administration from its traditional to a modern one, mandating a foreign tongue without learning the “inferior” local language, and forcefully converting natives to Christianity.

Upon this foundation, the Dutch legitimised rule through their Roman-Dutch law, which continues to regulate justice in Sri Lanka today. They also introduced the registration of births, deaths, and marriages, compulsory schooling, printing presses, wood carving, canal technology, transport systems, and social service centres.

The British rule in Sri Lanka introduced centralised administration, English-educated Sri Lankans, extended Burgher communities, and Tamil immigrants, making the island a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, and multi-religious nation. It is easy to assume colonialism “helped” Lankan society — until one personally meets oppression in the name of go(o)d.

Religion

Spreading holy words and guiding people towards better thoughts are common aspects of religions. But doing them by force was the choice of the colonising minds. Under Portuguese rule in Sri Lanka, Roman Catholic missionary activity led many Sri Lankans to adopt Portuguese surnames such as Perera, De Silva, Fernando, and Dias, among others. This practice will catch your attention today, amongst the one in ten people you meet in Sri Lanka. Then came the Dutch with their Protestantism to counterbalance the Portuguese Catholics.

English Language

Under British rule in Sri Lanka, classrooms became instrumental grounds where Christianity served as the base for education, and the dominating Catholic institutions in turn paved the way for the English language to reach the masses. English was not an option — it became mandatory to seek well-paying jobs that served as intermediaries between the ruler and the ruled. It is also said that the lasting prestige and social divide that English created are among the poisonous weeds that shaped post-independence politics. So, while the Portuguese influence introduced loanwords into daily speech, the English language made the people associate intellectualism and privilege with it.

Loanwords

The Sinhala months that go like “Janawāri”, “pebravari”, “mārthu”, and so on, are a good example of how English became rooted amongst the Sinhalese. But that is a much smaller percentage compared to nearly a thousand Portuguese-origin words found in everyday Sinhala and Sri Lankan Tamil. E.g. almariya (armário – wardrobe), annasi (ananás – pineapple), bonikka (boneca – doll), bottama (botão – button), gova (couve – cabbage), kalisama (calças – trousers), kussiya (cozinha – kitchen), lensuwa (lenço – handkerchief), narang (laranja – orange), paan (pão – bread), cadju (caju – cashew), salada (salada – salad), etc.

The Education System

Besides language and religion, even the educational approach fell into the colonisers’ shadow. A British tourist visiting Sri Lanka may casually chat about their O/L (Ordinary Level) and A/L (Advanced Level) days with their guides without having to translate standards, as Sri Lanka still follows the British scholastic hierarchies. Religion and life skills classes introduced by the British continue to be prevalent in Sri Lankan schools. Interestingly enough, such classes have been crucial in reviving Buddhism in West and South Sri Lanka and Hinduism in North and East Sri Lanka, post-independence.

Baila, Blouse, Bat, and Bread

It is 1996. The island, once colonised by empires, lifts the trophy in a sport that originated in the coloniser’s homeland. The national cricket team beat the England cricket team in the World Cup quarter-final—236 for 5 in just 40.4 overs against England’s 235 for 8. Sri Lanka had officially beaten England at their own game.

Apart from the once-leisurely sports like cricket, rugby, and golf, the colonial influence on Sri Lankan culture heightened when colonisers also blended Afro-Portuguese ballroom beats, such as Baila, into local rhythms, to the extent that you can feel them pulsating at almost every party and wedding in Sri Lanka today, forming a uniquely Sri Lankan music genre. Similarly, the formal wear in Sri Lanka — skirt and blouse for women, pants and shirt for men — is also an everyday reflection of the colonial threads that cling to the Lankan skin.

But nothing reveals the intimacy of colonial influence quite like what ends up on the plate. Take the humble chilli or “miris”, as Sri Lankans call it. Adopted so completely that it feels native, this crimson spice colours almost every curry on the island. Yet it was not born in Sri Lanka at all; the Portuguese took it there, along with pão (paan or bread). Today, a breakfast of bread and sambol (made out of coconut and chillies) feels so quintessentially Sri Lankan that few would guess its foreign origins.

Similarly, the popular lamprais, lingus, pastries, and kokis trace their roots to the Dutch Ceylon. Beyond the food itself lies a term called “short eats”, distinctly used in Sri Lanka alone, probably inspired by the British “afternoon tea”, which refers to savoury items. And of course, no reflection on Sri Lankan cuisine is complete without its most famous export: Ceylon tea. Ironically, this emblem of national pride was not born on the island at all; The British planted it with saplings from China. Over time, each of these imports — from Dutch, Portuguese, British, or otherwise — has been absorbed, transformed, and naturalised into something unmistakably Sri Lankan. Colonial tastes may have set the table, but the island made the feast its own.

Sri Lanka Post-Colonisation

Culture throughout history, across the globe, has never been constant, nor is it supposed to be. The colonial influence on Sri Lankan culture is just one of the many phases that has shaped it. The island’s identity does not solely lie in its religion, language, historical buildings, cuisine, sports, or fashion, but in what it has chosen to let go, hold onto, adapt, and adorn itself with.

In reality, there is no real “post-” to colonialism. The past is present. The island, like every other once-colonised land, will continue to live with an inherited modernity, an unconsciously adopted Western standard, lingering ethnic divides, markets ruled by foreign capital, and companies that mine its soil while selling back its own reflection.

Post the colonisation, post the civil war, and despite the ongoing economic crisis, with tourism as its lifeline, Sri Lanka has found its footing and is on a robust recovery path towards its glory. It is no easy feat to earn titles like “The Most Beautiful Island in the World” and “The Most Desirable Island in the World”. Although it sounds like the land naturally earned it, it is the conscious and collective will of the people who love their country, practise sustainability, celebrate the culture they grew up in, and welcome the tourists who share their love for the land.

Image sources: 1. sciencedirect.com, 2. Pinterest, 3. amazinglanka.com, 4. backstreetnomad.com, 5. lankaweb.com, 6. amazinglanka.com, 7. thuppahis.com